History of Saint Ignatius’ Church

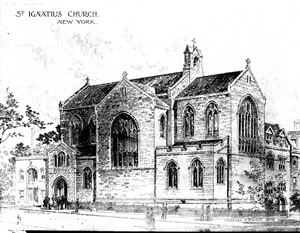

Original line drawing by Charles Haight

Our founding rector, Dr. Ferdinand C. Ewer moved from his Nantucket Unitarian-Quaker background to a boyhood embrace of the Episcopal Church. On occasion, he attended St. Thomas Church (on Houston Street and Broadway at that time) but turned away from Christianity and embraced quasi-transcendentalism during his years as a Harvard College undergraduate. After being graduated from Harvard in 1848, Ewer joined the ’49ers, and worked as a journalist in California. He also held a post with the San Francisco Board of Education. The earnest, honest searcher experienced a deep turning to Christ in a mining camp barroom conversion. With great determination, he pursued theological studies and was ordained a priest in 1858 in San Francisco, at Grace Church (now Cathedral). Ewer began his ordained ministry at Saint Anne’s Church for deaf-mutes in New York city under the rectorship of Dr. Thomas Gallaudet (who is remembered on our Church Calendar on August 27th) in 1860. He then followed a call to become rector of Christ Church, New York City, where he was considered an outstanding preacher.

The Parish of St. Ignatius was founded in December of 1871 by Dr. Ewer during a time that marked the height of Protestant and Roman Catholic antagonism here in New York. Dr. Ewer left his rectorship at Christ Church following a dramatic controversy over his defiant stand for the Catholicity of the Church, the centrality of the historic episcopate, and his devotion to the Anglo-Catholic Movement. Dr. Ewer died in Montreal, in dramatic circumstances, while preaching a sermon on Philippians 3:20: “For our conversation is in heaven; from whence also we look for the Saviour, the Lord Jesus Christ.…”

In the early months of the Parish, the congregation met in a rented building at 437 Seventh Avenue, between 33rd and 34th Streets before moving into a former Dutch Reformed Church at 54-56 West 40th Street facing Bryant Park. By the turn of the century, the surrounding neighborhood was beginning to lose its residential character, and many parish members had moved to the recently fashionable Upper West Side. Likewise, a cruciform church in a more scholarly Gothic manner would be necessary for the increasingly elaborate liturgy espoused by the then rector, Father Arthur Ritchie (Pennsylvania 1867, GTS 1871, and rector from 1884 to 1914)

Notwithstanding the strident objections of other Episcopal Churches in the area (of which there were six from 69th Street to 99th Street), Bishop Potter approved a move. Tradition holds that the bishop acquiesed because he was tired of arguing with Fr. Ritchie and was eager to get him out of his very visible mid-town location. A site 75 by 100 feet was bought at the present location—creating the space needed for liturgical processions—and construction began in 1901. Charles Coolidge Haight, the noted architect of collegiate and ecclesiastical buildings in New York and New Haven, and most famous for his work at the General Theological Seminary, was hired by the Parish.

Working within the strict boundaries of ecclesiology, Haight has made a great virtue out of the site’s greatest drawback, the lack of longitudinal orientation for a properly proportioned nave and transepts. The nave is a mere 35 feet wide (excluding the 6 foot wide aisles) and twice as long, and a full 66 feet high to the roof, through oaken tie beams with prominent carved knees. The “vestigial” transepts are nearly as wide as the nave itself by undecorated clerestory windows and from the north and west by monumental brilliantly colored stained glass windows. The chancel is as clearly separate as the canons of ecclesiology require, being cut off by means of three black marble steps, a masonry communion rail, and rood beam at the clerestory level. Yet the extreme separation of clergy and congregation implicit in cruciform designs with fully developed rood screens (such as that in the old St. Ignatius’ Church) disappears here. It is as though Haight were consciously tempering the severity of Anglo-Catholic sacramentalism by opening his great crossing to all the available light and presenting the chancel as an equally well-lighted stage, hardly separate at all, but sharing in the soaring volume of nave and transepts. The pictorial windows in the church were provided by the noted stained glass manufacturers John Hardman and Company of Birmingham, at some time before 1905, when an advertisement for the firm includes a section of the chancel window at St. Ignatius (Architectural Record, v.18—December, 1905, p.34).

On January 5, 1902, the first services were held in the crypt of the New Church, and on October 19 of the same year, in the newly completed building upstairs. Bishop Potter expressed his disapproval of the Catholic ritual of Saint Ignatius’ Church by his absence from the formal opening, although he readily gave assent to Father Ritchie’s request to invite Bishop Charles Grafton—a distinguished Anglo-Catholic prelate—of the Diocese of Fond du Lac in Wisconsin. Accordingly, Bishop Grafton was the Celebrant at Pontifical High Mass while Father George C. Christian of the Church of Saint Mary the Virgin delivered the sermon. From this time, there was at least an outward truce between Bishop and Rector, and it would appear that however strained their official relations, each personally respected and esteemed the other.

Relations between Father Ritchie and Bishop Potter improved and the parish grew under the rector’s firm leadership. Records show that St. Ignatius’ membership dropped soon after the election of a new rector, who invariably took the opportunity to institute even more “advanced” liturgical practices, thereby driving out a group of the more hidebound members of the parish. Their places were inevitably filled in short order, however, and the membership grew continually, if somewhat unsteadily. Father Ritchie retired in 1914, succeeded briefly by Father Maxwell Ganter, and then by Father William McCune, who took the implications of Catholic ritual even further, instituting a full Kalendar of Saints’ Days and the Devotions of the Stations of the Cross in 1920.

In October of 1920, the full Kalendar of Saints’ Days was adopted, as their commemoration was no longer restricted to the relatively few that were at that time named in the Book of Common Prayer. Unable to pay the sizeable mortgage on the new building due to unfilled hopes for funds from Father Ritchie’s will, St. Ignatius was not canonically consecrated until February 8, 1925. Much of the existing furniture and decorations date from this period, when the slightly enriched parish hired the celebrated Boston architects Cram and Ferguson to design decoration for the chancel, nave, and Lady Chapel.

The devotion of the Stations of the Cross began in Lent of the same year, and the present stations date back to 1926. The Statue of the Blessed Virgin Mary at the entrance of the Lady Chapel and the reredos and lamp in the chapel itself were added in 1924. The Statues of the Sacred Heart and Saint Ignatius were added in 1928, and the votive lamps in front of all three shrines were blessed in 1930. These statues were all designed by the distinguished architects Cram and Ferguson. The lamp before the Crucifix dates from 1936. The Angelus was first rung in January of 1930 and in November of the same year, the Baptismal Font was blessed. The altar, of white Vermont marble, was brought from the old church to the new location as were the flanking statues of Our Lady and Saint Ignatius.

After the Second World War, neighborhood demographics changed, Church membership dropped, and maintenance of the structure lapsed. With the construction of Lincoln Center twenty blocks south in the early 1960s, there began a gradual reinvigoration of the Upper West Side, and under the leadership of Rev’d Howard T. Stowe, membership increased, beginning a period of revitalisation that continues today. At this great time of social change, Saint Ignatius was among the first Anglo-Catholic parishes to welcome the ministry of ordained women. In 1980, the Rev. Ellen Barrett, the first openly gay woman ordained in the Episcopal Church, preached at Good Friday services; she was later invited to become an associate priest of the parish. The parish also experienced the wrenching heart ache and dislocation of the AIDS Crisis, seeing the loss of many beloved members, commemorated today with a shrine on the north aisle. Since then the parish has continued to grow in mission and ministry and through several successful capital campaigns has worked to improve and restore our historic building.

The Building and Its Grounds

Saint Ignatius’ Church is located in a neighborhood that was developed with brownstones (single family houses) in the 1880s and with successive waves of high-rise apartment houses in the 1930s and again in the 1950s. The Church building, designed by Charles Haight, is English Gothic in character, distinguished by its stained glass windows (from Birmingham, England, circa 1905), its Roman brick interior, and its gustavino ceiling tiles, which are interlocking and self-supporting. It occupies a lot measuring 75’ X 100’ and seats approximately 325 persons. The Church proper occupies most of the building. There is a tower that houses the Sacristy, a Library/Common Room and, on the top floor, a one-bedroom apartment with bath and kitchen. The basement contains a large Undercroft, two Sunday School rooms, an office and rehearsal space for the choirmaster, and ancillary storage space of forbidding appearance.

You can take a tour of our building here.

For more about the parish’s great nineteenth-century Patron, Charles Frederic Zabriskie click here.

For photos of the second rector, Fr Ritchie, taken by Charles Frederic Zabriskie click here.

For Photographs of the Church ca. 1905 click here.

For more details on the history of Saint Ignatius, see Louis Gray’s 1946 History of the Church

Also Project Canterbury documents about The Rev. Dr. Ferdinand Cartwright Ewer